by Arjan Verschuur, part of Court of Mother Earth

Introduction

Shortly after the presentation of the book Free, equal and living together by Damaris Matthijsen, I got a copy pressed into my hands. “Because what Damaris writes and what you here on Court of Mother Earth do so well together,” said Makke van Vollenhoven, who was the Social Art course at Economy Transformers followed and had a seasonal pitch at our campsite. And Makke was right. I read the book in one go and was immediately raving about it. Both about the many points of recognition, and the additional insights it gave me.

Much of the new insight related to what Damaris called the key Property mentions. While reading, I realised that we are on Court of Mother Earth - intuitively - had already made a start on making land ‘free’ or ‘of itself’, but that with regard to the ownership of labour and capital, we can still take some big steps so that ‘it’ ‘fits’ even better. In this blog, I focus on the production factor of labour. But for the sake of clarity of my story, I want to start with the land.

Ownership of land

Before we bought the campsite in 2016 that we have since Court of Mother Earth mention, we had a brainstorming session on possibilities of crowdfunding part of the purchase. While we were working on that, one of the initiators had this inspiration: “Give the Earth back to itself!” We were all silent for a moment. Not because it was such a great payoff for our crowdfunding campaign, but because in that moment we all felt how true it is that the Earth belongs only to itself. And that it is a precious illusion that we can own parts of the Earth. So after buying the campsite, we immediately removed the land from private ownership. We did so by legally owning the land under Court of Mother Earth under a foundation. The foundation leased the land to a cooperative on condition that the cooperative managed the land in an ecologically responsible manner. And finally, it is residents and guests who have leases that regulate that they can enjoy - individually and together - the usufruct of (parts of) the land. Even before we knew the concept of ‘triple ownership’, on Court of Mother Earth the ownership of the land is thus already threefold shaped.

Triple ownership

I recently attended a presentation by Jac Hielema on a ‘Capital Body for Free, Equal and Living Together’ that they want to establish from Economy Transformers. During this presentation, I actually only really understood what with ‘triple ownership’ is the division of roles between the three owners. These three owners were referred to by Jac as: ‘creative owner’, ‘economic owner’ and ‘legal owner’. Innerly, I immediately linked these three terms to the division of roles between foundation, cooperative and residents and guests with regard to the land under Court of Mother Earth. Residents and guests jointly enjoy the usufruct of the land and thus have economic ownership. The cooperative is the company that is free to ‘farm’ the land as it sees fit and is thus creatively owner. And the foundation, which, as I wrote, is the legal owner, decides what the land may or may not be used for and should ensure that the cooperative (as creative owner) and residents and guests (as economic owner) have an equal voice in deciding this.

Inwardly, I also immediately linked the terms ‘creative owner’, ‘economic owner’ and ‘legal owner’ to the way we are on Court of Mother Earth settled the ownership of labour. And in the future could shape triple. For over a year now, we have been on Court of Mother Earth namely talking to each other about how to make a move from economically ‘self-sufficient’ to economically ‘co-sufficient’. The impetus to engage in this conversation was a flash of insight, which was preceded by four interrelated observations.

The first observation was that - despite the hard work everyone does - on the one hand, some members of our community actually have less than sufficient income, while there are others who have more than sufficient income to meet their living needs.

The second observation was that several members of our community - in order to earn sufficient income - are doing work that they neither like nor are good at. This is particularly evident in the work involved in renting out ‘our’ holiday homes. I have deliberately put the word ‘our’ for holiday homes between ‘...’, because these holiday homes are not jointly owned, but privately owned and are also rented out at their own risk and expense. And in doing so, anyone who rents out a holiday home performs all the possible activities that this entails.

The third observation was that some members of our community - due to the time and energy they put into work to provide for their personal income - often do not get to do work that they do enjoy and that they are good at and that would benefit other members of our community and/or the community as a whole as well.

The fourth observation was that all of us are actually always faced with the (impossible) choice of investing more time and energy in work for ourselves for which we are directly paid or in work for the community for which we are not paid, but which indirectly meets some of our material, social and cultural needs.

The flash of insight we had over a year ago was that all these observations are the result of the (obvious) way we earn our income, namely: every man for himself. And that by sharing all the work - which now each does for himself - in line with each person's talent across the whole group, we could all enjoy our work more and as a group earn more income than the current sum of our individual incomes.

But how do you arrange that?

Linking the concepts of ‘creative owner’, ‘economic owner’ and ‘legal owner’ instead of the concept of land to the concept of labour, I suddenly saw how we can do that. To make that clear, I will first make a brief foray into labour relations common in our society.

Triple ownership of labour

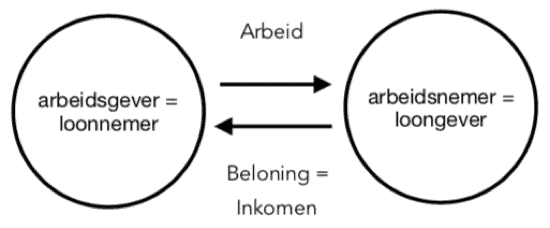

In today's economy, it is common for an ‘employer’ to hire an ‘employee’. The terms ‘employer’ and ‘employee’ contain an interesting inversion, by the way, because it is actually the ‘employee’ who - in return for payment of a certain remuneration - sells his work or labour power to the ‘employer’. So it would be more in line with the facts if we were to call the ‘employer’ a labourer and/or wage-earner and the ‘employee’ a labourer and/or wage-earner. Similarly, we can call a self-employed person a labour employer and his or her client a labour contractor. In both cases, Labour and Income are inextricably linked.

We can only break the (economic) need to exchange or sell our individual labour for an individual income, when we separate Labour and Income.

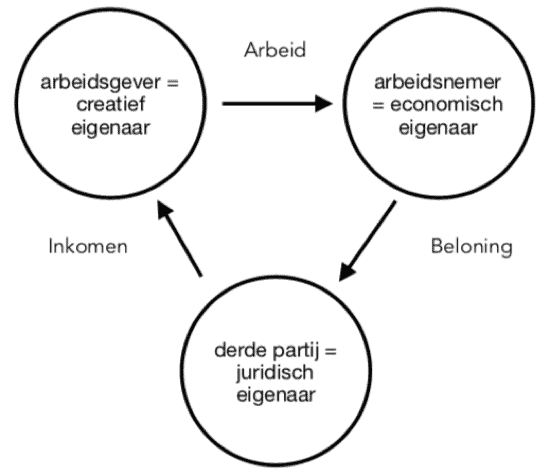

In order to separate labour and income, we need a third party, which instead of the labour employer receives the remuneration of the labour taker and instead of the labour taker pays an income to the labour employer. An income that need not be equal to the remuneration paid by the labourer, but - depending on the labourer's income needs - could also be lower or higher.

With this third party involved, we can create - as in the case of freeing up land and capital, also with regard to the labour production factor - a triple ownership structure. In this triple ownership structure:

- is the employer's creative ownership of his or her employment assets;

- the labour taker's control over the labour is limited to economic ownership (or: usufruct) of the labour result;

- and the third party becomes the legal owner of the labour remuneration (i.e.: the settlement for the work performed).

I can imagine that the concept of ‘legal owner’ in relation to ‘labour’ raises questions. I will therefore also briefly explain this combination of concepts. Again, I will do so using common (dual) employment relationships.

By hiring an employee, an employer becomes the de facto legal owner of his employee's work capacity. This is because an employer has the right to determine what work his or her employees should perform where, when and how. Thus, in this case, the employee/employer is only creatively owner of his work and the employer/worker is not only economically owner but also legally owner. The balance in the ownership of labour thus tips over to the side of the employer/ labour taker in this case.

A ZZP-er can - like an employee - sell his or her working assets, but usually a ZZP-er does not sell his or her working assets but the result of his or her labour or his or her labour performance. You could say that in the latter case, the self-employed person remains the legal owner of his or her work capability. The balance in the ownership of labour thus tips to the side of the employer in this case.

It follows from the above that in the case of triple ownership of labour, the third party's function is not only to separate Labour and Income, but also to ensure the balance between the creative ownership of the labour employer, on the one hand, and the economic ownership of the labour taker, on the other. This third party can do so by matching the needs of labour takers and the needs of labour employers - through proper consultation with both parties. In other words, the third party is a (social) balancing act.

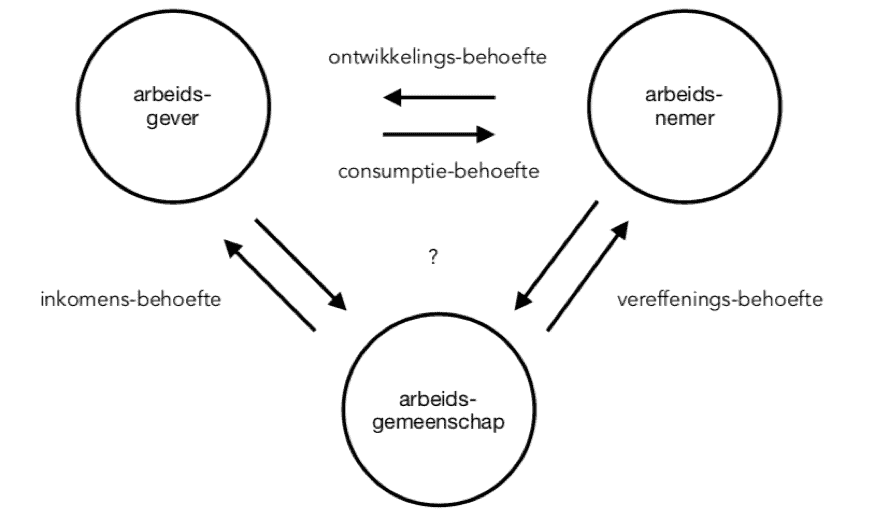

But what are - in a general sense - the needs of employers and workers that can be aligned through consultation in this balancing body?

With the labour performance that a labour employer provides, he or she (directly or indirectly) meets the consumption needs of the labour consumer.

By receiving - instead of the labour employer - compensation for the labour service, the third party can meet the settlement needs of the labour employer. With the compensation received, the third party can then meet the labour employer's income needs.

In today's labour relations, a labour employer is actually forced to be guided by his or her income need in relation to the labour taker. When the third party meets the labour employer's income need, the labour employer's development need can again come to the fore in relation to the labour taker. That is, the need to develop his or her talents and use them in a meaningful way to serve others.

In other words, the essence of the third party's function is to match, on the one hand, the (mental) developmental needs of the labour employer and, on the other hand, the (material) consumption needs of the labour taker as closely as possible. And thus, on the one hand, to prevent the labourer - from his consumption need - from exploiting the labourer's labour capacity, and on the other hand, to prevent the labourer - from his development need - from providing a labour performance that the labourer does not need at all.

But perhaps the third party itself has needs, which are met by meeting the income needs of labour employers on the one hand and the settlement needs of labour takers on the other?

If these needs are indeed there, it is obvious that they are to be found in the sphere of legal life. After all, the developmental needs of the labour employer lie in the sphere of spiritual/cultural life and the consumption needs of the labour taker lie in the sphere of economic life.

In the legal sphere, the principle of equality prevails. Meeting the labour employer's income needs does justice to the sense of law that every human being has an equal right to adequate food, clothing and shelter. However, how much income a labour employer needs to meet the livelihood needs of himself and those he/she cares for may vary. Both from person to person and over time. Thus, the sense of justice does not demand that every labour provider be given an equal and fixed income, but that each labour provider be given a variable income to suit his or her varying needs.

In relation to the jobholder, there is a sense of justice that equal performance should also be rewarded equally. Regardless of the situation an individual labour contractor finds himself in and the income needs he or she has in that particular situation. The third party can do justice to this sense of justice by charging labourers a so-called ‘market-compliant’ price for the labour services provided.

Now that we have a picture of the third party's legal needs, it also becomes clear who or what this third party is. Indeed, the needs in the legal sphere are not individual needs, but community needs. In other words, the third party is ‘a set of people working together’ or ‘a labour community’ or - in terms of Economy Transformers - ‘a Share Society’.

By paying equal compensation for equal services, the labour taker meets the one legal need of the labour community. And by settling for an income sufficient to meet the livelihood needs of himself and those he/she cares for, the labour employer meets the other legal need of the labour community.

And with the money that remains, when each of us does not - as usual - spend all-my-income-that-I-earn-with-my-work, collective capital can then be formed. And Jac can tell you more about that ;-).